The second interview of this series is with Professor Kenichiro Itami, a young researcher who is at the forefront of chemistry, who also happens to be this interviewer’s boss at Nagoya University. Professor Itami has been creating a variety of structures at the molecular level under the motto “synthetic chemistry is unified”.

[su_dropcap size=”2″]Q[/su_dropcap] What made you choose chemistry as a career?

[su_dropcap size=”2″]A[/su_dropcap]

I think it has to do with a certain line of reasoning that I have created for myself while studying for my university entrance exams. As a child, my hobbies were supercars, LEGO® and sports. While studying for my university entrance exams and needing to decide upon a future plan, I once read a newspaper article that stated that petroleum will disappear in our lifetime, leaving me in a state of shock. It made me think that my childhood dreams of driving around one of those exotic cars will never come true. Looking up matters more in depth, I learned that there is an attractive subject of study at the Department of Engineering at Kyoto University called “synthetic chemistry”. In its program description, it said: “The generation of new materials”. Through an acquaintance of my father, I had also heard that the synthetic chemistry program at Kyoto University was excellent. And then, I decided. That I wanted to join that synthetic chemistry program, and synthesize (for me, that meant “to LEGO®”) a new type of fuel that will replace gasoline. That it didn’t matter if I wasn’t very adept at studying, since I was good at LEGO® and I had endurance. I even got ahead of myself and decided to call this new fuel “itamine”. It’s a selfish line of reasoning created by a synergy of my exam studying and my hobbies, but this is really how I decided to jump into the world of chemistry. The only thing that I somewhat regret is that I had told my high school classmates about this. This must have given them a lasting impression, because many of them remember this quote of mine—so every time I attend a class reunion, they ask me: “Have you made ‘itamine’ yet?” Obviously, I have not yet made such a thing, and I’m starting to have a hard time attending these class reunions.

[su_dropcap size=”2″]Q[/su_dropcap]

If you were not a chemist, what would you like to be, and why?

[su_dropcap size=”2″]A[/su_dropcap]

This is a really tough question. I really love both my chemistry and my students, so it’s a perfect environment for me right now—I couldn’t think of any other career option. However, if I really had to think about it, it would have to be something that is equally exciting, in a job where making “things” and interacting with people are crucial. Maybe a visionary noodle shop owner? Sorry, that was my unbearable desire to eat ramen noodles that just came out right now.

[su_dropcap size=”2″]Q[/su_dropcap]

Currently, what kind of research are you conducting? Moreover, how do you foresee its future development?

[su_dropcap size=”2″]A[/su_dropcap]

The research we are conducting involves both elementary and applied organic chemistry and synthetic chemistry. We have been pursuing the following ideals in interdisciplinary fashion: “To furnish organic compounds that everyone desires, in a manner that everyone hopes to achieve”; “to generate medical and agrochemical compounds, as well as complex natural products and functional materials”; and “to build up molecular complexity in unprecedented manner”. At first glance, it might seem like I am targeting everything in all of organic chemical space, like an unfocused research proposal. However, there is a clear vision behind this, and I purposely aim for this kind of research group. Most importantly, I dislike the labels that chemists are often ascribed, like “the catalysis person” or the “materials person” or the “natural product person”, and there are advantages in conducting multidisciplinary research in synthetic chemistry. Firstly, I believe that many related fields of chemistry are trying to find solutions to similar problems, and that there are advantages to sharing knowledge. Furthermore, I believe that this sort of research program would aid in the development of all individuals of our laboratory, including myself. And lastly, under our motto of “synthetic chemistry is unified”, I wish to contribute, even a little, to the construction of a new paradigm in synthetic chemistry. Perhaps the above sounds a little showy, but in basic terms, I simply want to play with a lot of “molecular LEGO®”. For a further piece of our group’s philosophy, I leave to you our laboratory ideals: “We want to be an organic chemist… who is touched by nature’s beauty, who loves molecules, who speaks their dreams. “We want to be a master of creation… who is appreciated by people, who is indispensable. “We want to be a research group… that generates value by linking molecules, that generates social rings by linking people. “This is our wish, our hope, our dream.” Whenever we attempt to translate the above (from its Japanese original) to an extremely simplified English motto, it somehow becomes “work hard, play harder!”…

[su_dropcap size=”2″]Q[/su_dropcap]

If you could have dinner with any famous person from the past, who would it be, and why?

[su_dropcap size=”2″]A[/su_dropcap]

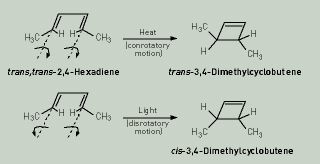

A: Within the field of chemistry, I would list Professors Kenichi Fukui, Robert B. Woodward and Yoshimasa Hirata. Professor Kenichi Fukui was one of the reasons why I wanted to gain admission to the Department of Chemistry at Kyoto University. I have always admired the beautiful chemistry logic presented in his frontier molecular orbital theory. Moreover, one of my favorite books is Professor Fukui’s “gakumon-no-sōzō” (学問の創造, roughly translated as “the creation of learning”). As for Professor Woodward, I first learned of him when I studied the Woodward–Hoffmann rules along with frontier molecular orbital theory in undergrad. I was utterly impressed with the Woodward–Hoffmann rules, which shed light on a series of pericyclic reactions whose stereospecificity was a true mystery at the time. Thereafter, he developed the Woodward–Fieser rules in UV absorption, artistically completed the total synthesis of numerous natural products, and deduced the structure of ferrocene. Hearing all these feats, I truly thought that it is humanly impossible to be that good at what he does! I have heard of many legendary stories about him, but I would have liked to see that with my own eyes. Finally, Professor Yoshimasa Hirata is considered to be the “father” of the Department of Chemistry at Nagoya University where I work. How did he create the famous “Hirata School”? How did he “produce” such unique and wonderful scientists, represented by Professors Koji Nakanishi (Columbia University), Yoshito Kishi (Harvard University), Goto Toshio (Nagoya University), Daisuke Uemura (Nagoya University and Keio University) and Osamu Shimomura (Boston University)? I would like to learn the secret behind these achievements. He is truly an exceptional educator and he is someone I really look up to.

[su_dropcap size=”2″]Q[/su_dropcap]

When was the last time you performed an experiment in the laboratory, and what was it about?

[su_dropcap size=”2″]A[/su_dropcap]

A: The last entry in my laboratory notebook is from three years ago. However, every year, when the new undergraduate seniors come into our laboratory for the first time, we show them how to run experiments for about two weeks. We use the Suzuki–Miyaura coupling as a model reaction, and we show the students how to set up the reaction, how to follow the reaction progress, how to separate and purify the desired product, and how to conduct structural analysis. I used to run these reactions myself and I used to tell them annoying things like: “See, your yields can never surpass mine”. But I no longer do that. Sometimes I go bother my students when they are having difficulties obtaining single crystals for X-ray analysis, but my success rate is very low, so these days I don’t do that either. I’m a little irritated with myself that I can’t conduct experiments like Professor Koichiro Oshima (emeritus professor, Kyoto University), who I respect very much.

[su_dropcap size=”2″]Q[/su_dropcap]

If you were stranded on a desert island, which book or song/piece of music would you like to have with you? Please single out your favorite example.

[su_dropcap size=”2″]A[/su_dropcap]

A: I would bring the “Appetite for Destruction” CD by Guns N’ Roses. I have always listened to hard rock and heavy metal ever since my elementary school days. I still remember the impact “Appetite for Destruction” had on me when I was still in high school, and I still listen to it occasionally. A certain non-Japanese professor who knows that I’m a Guns’ fan even sends me Guns’ merchandise! I have come to realize during this interview that I would probably not find it sufficient to bring one CD, and I would rather fill up my iPod and bring it all along… [amazonjs asin=”B000000OQF” locale=”US” title=”Appetite for Destruction”]

[su_dropcap size=”2″]Q[/su_dropcap] Do you have any suggestions as to whom we should interview next?

[su_dropcap size=”2″]A[/su_dropcap]

A: If I were to choose scientists from my generation, it would be Professors Jun Terao (associate professor, Kyoto University) or Tetsuro Murahashi (associate professor, Osaka University); among scientists that are a little bit older than me, Professors Takashi Ooi (professor, Nagoya University), Motonari Uesugi (professor, Kyoto University) or Motomu Kanai (professor, The University of Tokyo); among those that are slightly older, Professor Itaru Hamachi (professor, Kyoto University); among those that are even older, Professor Keisuke Suzuki (professor, Tokyo Institute of Technology), Professor Eiji Yashima (professor, Nagoya University) or Dr. Terunori Fujita (executive director of research at Mitsui Chemicals); and finally, among those that younger than me, Professor Atsushi Wakamiya (associate professor, Kyoto University) or Professor Makoto Yamashita (associate professor, Chuo University). My apologies for listing so many names, but all these people are unique and passionate researchers. Finally, I have a favor to ask you. I’m a big fan of Chem-Station, and it is absolutely true that this website helps generate chemistry enthusiasts. I thank the Chem-Station staff who run the website from the bottom of my heart. Please continue to increase the number of chemistry lovers and molecule lovers through Chem-Station.

Biographical sketch of Kenichiro Itami:

Born on April 4, 1971. Professor, Graduate School of Science at Nagoya University. He specializes in organic chemistry, synthetic organic chemistry, and molecular catalysis. Japanese version written here on date;8.12. 2010